Much has been made of Jane Austen's early love, Tom Lefroy, purportedly wearing a white coat in emulation of Henry Fielding's racy literary hero, Tom Jones. However, the only authority we have for this is Jane herself, who, as a mistress of the art of the double entendre, ought not always to be taken literally. In Jane's earliest surviving letter to Cassandra, we hear that Lefroy:

Much has been made of Jane Austen's early love, Tom Lefroy, purportedly wearing a white coat in emulation of Henry Fielding's racy literary hero, Tom Jones. However, the only authority we have for this is Jane herself, who, as a mistress of the art of the double entendre, ought not always to be taken literally. In Jane's earliest surviving letter to Cassandra, we hear that Lefroy:“has but one fault, which time will, I trust, entirely remove—it is that his morning coat is a great deal too light. He is a very great admirer of Tom Jones, and therefore wears the same coloured clothes, I imagine, as he did when he was wounded.”

In Fielding's novel, Tom Jones incurred his wound in a singular manner: he volunteered to enlist in an army regiment, and in a round of after-dinner toasting and merrymaking, one Ensign Northerton jested about the allegedly loose morals of Jones’ beloved Sophia Western: “Tom French of our regiment had both her and her aunt at Bath” - among several other such slurs on her character. This was too much for Jones, who sprang to her defence, accusing Northerton of being an impudent rascal, which promptly earned him a bottle of liquor hurled at his head. Northerton, it turns out, had heard no such thing of Sophia, but was merely retaliating for an earlier jest by Jones. [Tom Jones, Book VII, Chapter XII]

In Fielding's novel, Tom Jones incurred his wound in a singular manner: he volunteered to enlist in an army regiment, and in a round of after-dinner toasting and merrymaking, one Ensign Northerton jested about the allegedly loose morals of Jones’ beloved Sophia Western: “Tom French of our regiment had both her and her aunt at Bath” - among several other such slurs on her character. This was too much for Jones, who sprang to her defence, accusing Northerton of being an impudent rascal, which promptly earned him a bottle of liquor hurled at his head. Northerton, it turns out, had heard no such thing of Sophia, but was merely retaliating for an earlier jest by Jones. [Tom Jones, Book VII, Chapter XII]The point has already been made on this blog that it is likely that an Austen family tradition existed concerning Jane Austen's resemblance to Fielding's heroine, Sophia Western. In Tom Jones, the specific reference to the white coat occurs when Jones is recovering from his injury:

As soon as the sergeant was departed, Jones rose from his bed, and dressed himself entirely, putting on even his coat, which, as its colour was white, showed very visibly streams of blood which had flown down it.[Tom Jones Book VII, Chapter XIV].

Austen biographer Jon Spence has given us a further example of Fielding’s use of wounding as a metaphor for being in love. In what is an extremely convoluted plot, Jones engages in a duel with a Mr Fitzpatrick, who wrongly believes that Jones is consorting with his wife, who is in fact lusting after Jones. Jones nearly kills Fitzpatrick, and is subsequently visited in prison by a Mrs Waters.

Earlier in the novel Mrs Waters had gone to Bath in the company of various Irish gentlemen, including Fitzpatrick, who from then on successfully passed her off as his wife (Fitzpatrick’s real wife was the cousin of Sophia Western). Mrs Waters has also once been in love with Jones:

“It was some time before she discovered that the gentleman [Jones] who had given him [Fitzpatrick] this wound was the very same person from whom her heart had received a wound, which though not of a mortal kind, was yet so deep that it had left a considerable scar behind it.” [Tom Jones Book XVII Chapter IX]

However, judging by the remainder of her interaction with Jones, it is by no means certain that her heart has in fact recovered from its wound.

I have already commented in an earlier post that Tom Lefroy’s purported admiration of Tom Jones need not be taken as incontrovertible fact. Fielding was a known favourite with the Austens, who had previously put on family theatrical performances of at least one of his works (Tom Thumb).

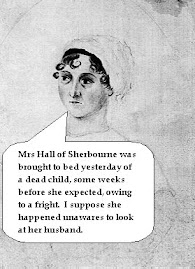

Given the numerous references to characters and situations from Tom Jones throughout Jane Austen’s novels, it is just as likely that it was Jane Austen herself who admired Tom Jones, despite what her brother assured the public after her death, when it became incumbent on the family to start protecting her ladylike reputation. Jane's talk of the Toms Lefroy and Jones and their white coats may well have been was a coded reference for Cassandra’s eyes only.[1]

If so, it would have been by no means the only time that Jane Austen employed a literary reference as a metaphor for her own situation. In a later letter she explicitly likened being stuck at her brother’s house with no means to get home again, to the plight of Fanny Burney’s heroine Camilla, stuck in a summerhouse without a ladder to get out.

Note:

[1] Linda Robinson Walker suggested the idea of a coded reference, although I believe it is more sophisticated than the one she puts forward. Jon Spence (Becoming Jane Austen) has pointed out a few character names from Tom Jones also employed by Jane Austen in her novels, although there are several more that have not been listed by him. One of the most telling examples is perhaps “Willoughby”, a surname from Jane Austen’s maternal ancestors but also the real life Justice Richard Willoughby, who appears in Book VIII, Chapter XI of Tom Jones. Readers of Sense and Sensibility may draw their own conclusions, or not, as they please.